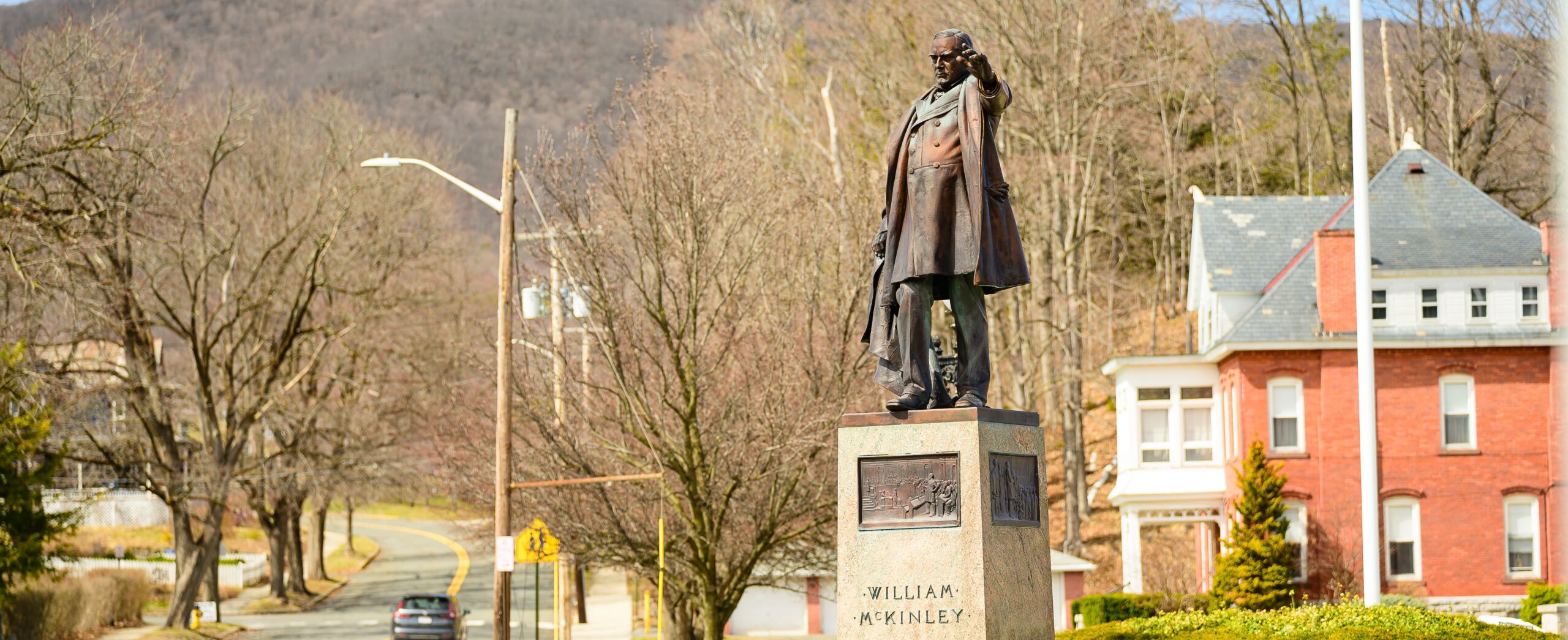

The William “Major” McKinley’s statue has been a pillar of downtown Adams, Massachusetts, for one hundred and twenty years. Occupying one end of Park Street, the town’s main thoroughfare, the statue, with an arm outstretched, welcomes travelers from the north and provides a rotary for others. President McKinley continues to watch over Adams from his vaunted position as he did so many years ago.

McKinley was the third president assassinated within thirty-six years. Abraham Lincoln in 1865, James Garfield in 1881 (on his way to Williams College, his alma mater to speak), and McKinley in 1901. A little more than two years after his death, the small town of Adams, with a population of 11,000, was one of only two towns to erect a statue in his honor.

Now more about the man and his connection to Adams.

McKinley, born January 29, 1843, was the seventh of eight living children. His father, William Sr., worked and managed iron foundries in Niles, Ohio. His mother was Nancy Allison-McKinley, a devout Methodist who was a strong proponent of education.

During his early childhood, under the tutelage of his Methodist teacher and his mother’s devoted attention, McKinley learned the value of study and hard work. He also helped with the family chores, taking the cows to the pasture, working in the garden, and helping his dad at the foundry.

After completing his studies at the Methodist school at seventeen, he attended Allegheny College for a year, where he thrived and became involved in campus life. On campus, the issue of slavery was a contentious topic. McKinley was resolute in his abolitionist feelings as was his family.

Health issues and family finances required him to leave school after a year and return home where he found work as a postal worker and then as a teacher earning $25.00 a month.

While he was teaching, Fort Sumter was bombarded by the local militia on April 12 and 13, 1861 and the overwhelmed federal soldiers surrendered to Southern forces on April 14, 1861. McKinley decided it was time for him to join the Army.

He enlisted in June 1861 at eighteen as a private in the 23rd Ohio Volunteer Infantry. He was assigned to the quartermaster corps and quickly recognized as possessing a logistical knack for finding and getting supplies to the troops. At one point he was promoted to commissary sergeant.

McKinley was recognized several times for bravery during the battle at Antietam in September 1862. The first day of the two-day battle on September 17 was known to be the “bloodiest day in American history,” where over 22,000 soldiers were killed, wounded, or missing.

During this carnage, Commissary Sergeant McKinley displayed uncommon bravery while under fire, delivering food and critical supplies to his decimated regiment. He was also noted to have ridden under a torrent of bullets and artillery fire to deliver messages to forward commanders. As a result of his bravery, he was promoted to 2nd Lieutenant.

He continued to fight with General Sheridan’s Army until the end of the war. He was promoted to captain and then breveted to major for gallantry in action in West Virginia and Shenandoah. After serving four years in the Army, he returned home, and his friends adopted and began calling him by the nickname of “Major.”

After his discharge, McKinley left home to study law at Albany Law School in New York for one year. Returning to Ohio, he passed the bar exam and opened a law practice in Canton, Ohio, making no secret of his desire to serve in Congress.

His political career began with successfully being elected district attorney in 1869, and he continued to maintain a thriving law practice.

McKinley successfully ran for Congress in 1876 and decided to become an expert on tariffs an ever-increasing important topic with the growth of American industry. During his next fourteen years in Congress, he mastered a large amount of tariff information, becoming the House’s expert.

McKinley had decided that protectionism was necessary to protect growing American industries. The tariffs covered hundreds of items, including woolen, cotton, and linens. Items would ultimately affect the future of many mill-towns-including a place called Adams.

The McKinley Tariff was passed into law in 1890, dramatically increasing the tax rate on foreign products. Business owners strongly supported this legislation. While it encouraged industrial development and meant more jobs, it also increased the price of goods, which did not always sit well with many Americans.

McKinley ran for and was elected governor in 1892 and re-elected once, serving until 1895. During his time in office, the State’s tax system was improved; a railroad safety law was sanctioned; a state board of arbitration was established; and while he was a friend of labor, he quickly ended a coal miners’ strike.

During his time as governor, McKinley met the wealthy, powerful, influential industrialist William Brown (W.B.) Plunkett, and they become friends. Plunkett, a mill owner and operator supported McKinley’s strong advocacy of tariffs to protect American manufacturing and his family’s business.

Using his success as a governor for a platform focused on tariffs, gold currency, and restricting trusts/monopolies, McKinley ran against Willian Jennings Bryan for the United States presidency and won a decisive victory becoming the nation’s 25th leader in 1896.

McKinley would grow the nation’s standing Army and develop its Navy as he began dealing with many international affairs foreign to previous presidents. He continued to take a firm stance on protectionism but realized that as America’s industries flourished, they needed outlets for their goods.

During his presidency, McKinley tried to avoid being involved in Spain’s troubles with an insurgency in Cuba. His hands-off or diplomatic approach didn’t work, conditions worsened in Cuba, and Congress was a stronger supporter of the insurgents at the time.

When the USS Maine was sent to Cuba to protect American citizens as part of McKinley’s diplomatic efforts and then sunk with a huge loss of life, McKinley was pushed to ask Congress to declare war in 1898. In a matter of months, Commodore Dewey destroyed most of the Spanish fleet, and the U.S. Army captured Santiago and neighboring Puerto Rico another Spanish possession.

Spain quickly sued for peace, left Cuba, gave the U.S. Puerto Rico and Guam as reparations for the war, and ceded control of the Philippines. In a matter of months, Spain lost most of its overseas empire, and the U.S. became a global power.

During this same time, in the late 1890s, other countries were looking at occupying Hawaii. McKinley realized the Islands’ strategic importance and, with Congress’s help, passed legislation annexing Hawaii.

ADAMS/THE PLUNKETT’S

The Plunketts have a long history in Adams. William Caldwell Plunkett arrived in 1829 and quickly became the owner of a cotton and woolen manufacturing company. His two sons, William Brown (W.B.) and Charles Timothy (C.T.), both slightly younger than McKinley, formed the W.C. Plunkett and Sons Company in the early 1880s.

W.B. Plunkett, active and interested in politics, became a friend and a political backer of William McKinley, who, with his protectionist efforts, would significantly affect the success of the Berkshire Mills and, consequently, Adams for the next seventy years. The men became such good friends that McKinley visited W.B. three times while in public office. Once during his term as Governor of Ohio and then as the President.

During his first visit in October 1892, Governor McKinley attended dedication ceremonies and laid the cornerstone for Berkshire Cotton Manufacturing Mill # 2. It was quite a celebration with 3000 people attending, followed by a dedication ball and concert.

McKinley would always stay at W.B.’s mansion on Park Street, now the Adams Town Hall. He often strolled across town to visit C.T. Plunket, who lived on Maple Street, greeting citizens along the way. McKinley seldom, if ever, had security accompany him.

McKinley returned to Adams after being elected as President in September 1897. This time with several of his cabinet members and spent ten days at the Plunkett house on Park Street. For a time, Adams was the seat of the government of the United States. It was during this visit that he laid the cornerstone for Adams Library.

His 3rd and last visit was in June 1899 when he laid the cornerstone for Mill # 4. McKinley only spent four days in Adams, needing to return to the White House because his wife was ill.

Note (Adams Historical Society Newsletter-August 2018)

“The Berkshire Cotton Manufacturing Company operated the largest mills to have ever operated in Adams…. From 1889 to 1958, it produced broadcloths and fine cotton fabric.

W.C. and C.T. Plunkett took advantage of the price protection offered by the McKinley Tariff of 1890 to expand four times over the next eleven years. Creating the greatest economic prosperity in the history of Adams, the company was the fountainhead of commercial development on Park and Summer Streets, the construction of schools and churches, the expansion of a multi-ethnic population, and the residential construction necessary to house it.

Just slightly over twenty-four months after his last visit with the Plunkett’s, the newly re-elected President gave a speech to an estimated 50,000 people at a Pan American Exposition in Buffalo, New York. Afterwards, McKinley began shaking hands with those in line.

It was not long before a young man whose right hand was wrapped in a handkerchief approached the President. McKinley reached out to shake his uninjured left hand when the assailant fired point-blank shots into McKinley’s abdomen.

The man, soon identified as Leon Czolgosz, had recently lost his job, turned to anarchism, and blamed McKinley for his employment problems.

McKinley, blood quickly appearing on his white vest, staggered backward, was sat down and eventually placed on a stretcher and brought by ambulance to the Fair’s hospital.

A quick examination showed one bullet hit a button and grazed him, and McKinley found it in his clothing: the other penetrated his abdomen and other organs. It was decided he needed to be operated on immediately.

The Fair’s hospital was not equipped to deal with serious injuries. It lacked the equipment and lighting and needed to look for a surgeon. Once a doctor was located, McKinley was medicated with ether, and then the doctor cut into his abdomen in the fading light of the afternoon.

He struggled because of the President’s girth but did find entrance and exit holes in his stomach which he sewed up. The surgeon could not find the bullet, presumed it was lodged in his back muscles, and decided, based on the thought at the time that the bullet would do little further damage, to close the wound. Note: Although he could find any additional damage, low-velocity bullets for pistols usually did considerable damage to organs.

Hearing of the President’s condition, Thomas Edison sent a primitive x-ray machine from New Jersey to a nearby hospital with the hopes it might help locate the bullet, but much to his chagrin, the machine was missing a part and never used, and the bullet was never found.

McKinley was moved to a nearby house, began to recover, and positive news was released to the public. It was a false hope; the nearly sixty-year-old, overweight President would gradually fall victim to creeping gangrene from infection of an uncleansed wound. Over the next six days, his condition worsened as the gangrene spread, and he became unconscious toward the end. In the early twentieth century most patients died from gunshot wounds to the abdomen, usually from gangrene.

At 2:15 am on Saturday, September 14, 1901, McKinley died almost eight days after being shot. An autopsy revealed the bullet had passed through the stomach, colon, and kidney and damaged the pancreas. An autopsy was conducted but his wife Ida, severely distressed, demanded it be stopped after four hours.

The Town of Adams was shocked at the death of the friendly man who had walked their streets, greeting and shaking hands with everyone, and who had been an enormous benefactor to the mills many worked in.

The assassin’s trial began less than two weeks after the President’s death. During the two-day trial, Czolgosz was found guilty after a half hour of deliberation by the jury. The judge sentenced him to death by electrocution. Czolgosz was executed with 1700 volts of electricity on October 29, 1901.

After the President’s death, the Plunketts desired to honor McKinley, their friend and benefactor, who did so much for Adams. They supported a drive to fund the creation of a statue in his honor. Contributions came from schools, churches, and manufacturing companies. Augustus Lukeman, a noted sculptor from New York, was chosen to create his statue.

The resulting eight-foot bronze statue rests on a granite pedestal and was unveiled on October 10, 1903, during a huge dedication ceremony. The towering figure has its left arm extended to represent McKinley during a speech in Congress pushing through the tariff bill.

The dedication was a huge event for the town. The State’s governor and lt. governor were in attendance and many other local officials (mayors and selectmen) from nearby towns. A special train from North Adams and crowded trolley cars delivered crowds of people to the dedication. A huge platform, patriotically decorated, was constructed on the terraces in front of the Adams Free Library.

The towering statue had tablets attached to each of its four sides and is described in a Transcript article date October 10, 1903.

The four tablets have been most appropriately selected and significantly inscribed. Each plate is 20 by 30 inches. On the front is a plate showing the President in the halls of Congress and inscribed “William McKinley addressing the House of Representatives on the Measure which became famous under his name” and refers to the McKinley tariff bill. Beneath this tablet is inscribed in bronze letters, the name of him in whose honor the memorial was erected “William McKinley.”

The tablet on the west side of the pedestal is inscribed “William McKinley, commissary sergeant at the Battle of Antietam, MDCCCLXIL.” It shows a war scene, with the late President as a young man driving a commissary wagon and refers to an incident during his civil war service.

The tablet on the rear or south side of the pedestal is inscribed. “Let us remember that our interest is Concord, not Conflict, and our real eminence is the Victories of Peace, not those of War.” Those words were taken from his speech at Buffalo and at the bottom of the tablet is inscribed “From President McKinley’s address at Buffalo, September VI, MDCCCI.”

The tablet on the east side of the pedestal is inscribed “William McKinley delivering his address at his first inauguration as President of the United States. March IV. MDCCCXCVIL.” It depicts him standing on a balcony overlooking the steps leading to the Capitol in Washington, D.C.

President McKinley who presided over America’s conversion to a global power now was a towering figure presiding over Adams’s main thoroughfare.

His assassination created a huge sense of loss for both Adams and the United States.

Photo Credit: Dan Morgan Photography